[Updated, August 2025]

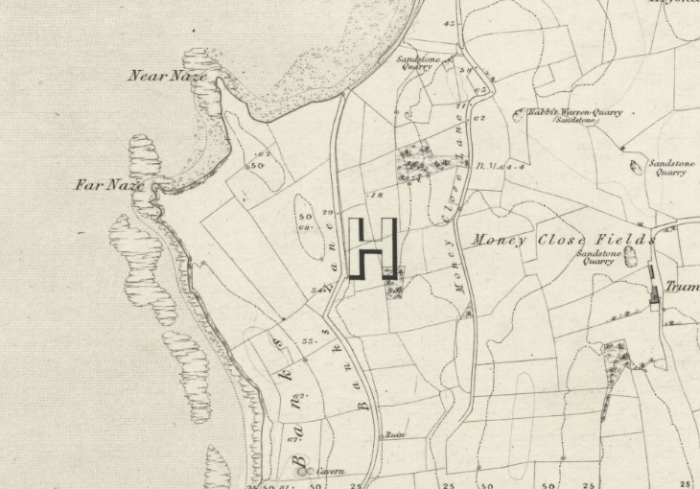

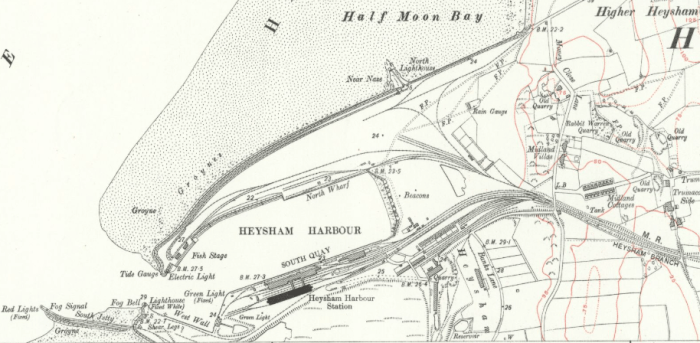

In the 1890s the Midland Railway settled on Heysham as the location for a harbour to give it access to Irish Sea trade and routes to Dublin and Belfast.

The historical background to this and the nature of the construction have been well covered by others; such as by Lancaster Civic Vision Guide 92 [available online at: www.lancastercivicsociety.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/92-Heysham-Harbour-2022.pdf ]

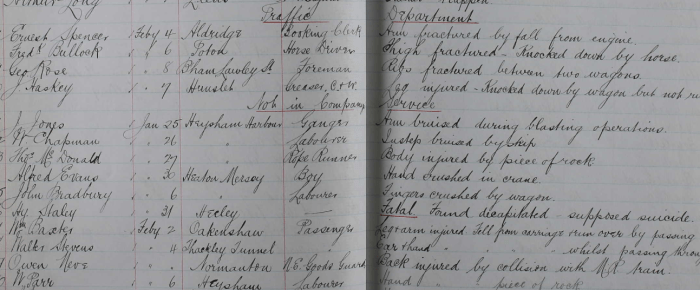

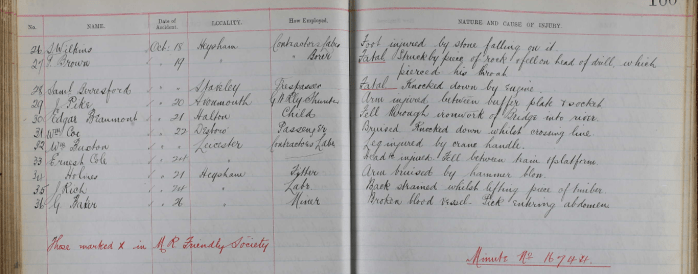

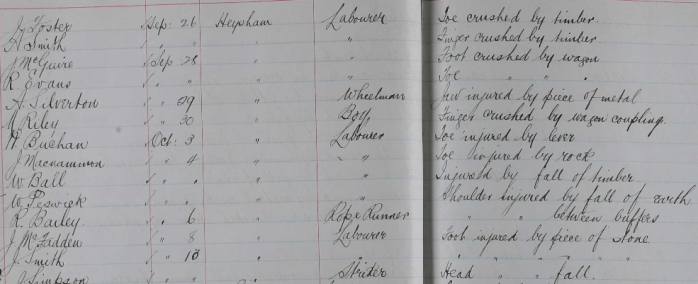

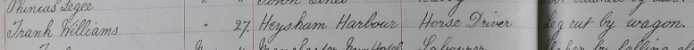

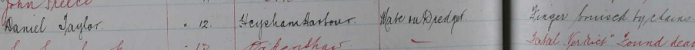

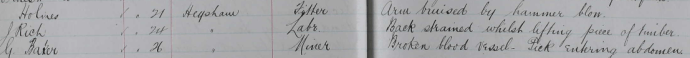

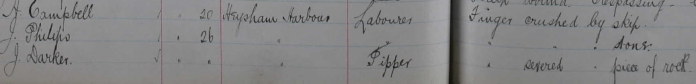

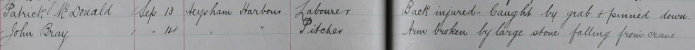

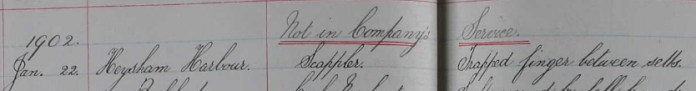

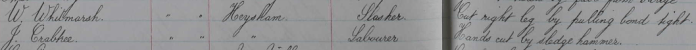

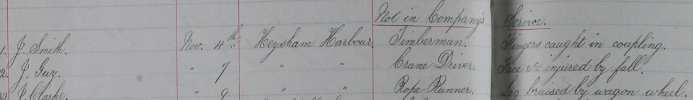

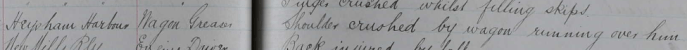

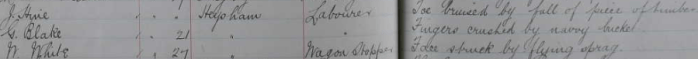

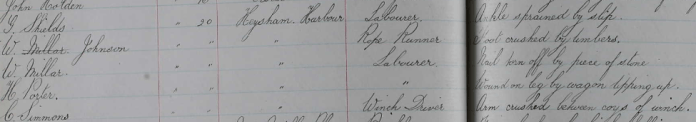

The aim of this piece is to look at the human cost of the construction of Heysham Harbour. The information has been obtained through an online search of a ledger which lists injuries on the Midland Railway from 1895 to 1920, then cross checked against data made available by the Portsmouth University “Railway Work, Life and Death” Project https://www.railwayaccidents.port.ac.uk/. The works on the harbour at Heysham began in the latter part of 1897 and the port was operational by the end of 1904. This is reflected in the occurrence of injuries to the workforce. The first mishap affected a S. Bristow, a locomotive driver, who on the 9th October 1897 suffered a leg crushed between a wagon and an engine. Injuries to construction staff diminish quite rapidly towards the end of 1904 and accidents thereafter are distinctly different affecting staff operating the port.

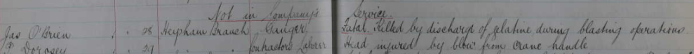

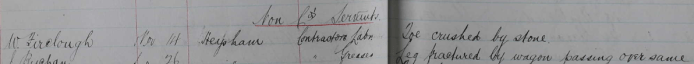

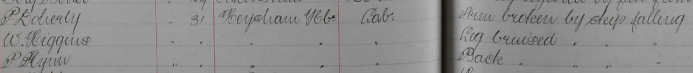

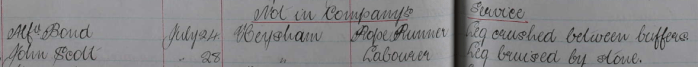

The Midland Railway appears to have been meticulous in recording injuries occurring on its network. This included staff not directly employed by the railway such as those working for contractors; as at Heysham. In the records these are listed under “Not in Company Service”.

Information ranging from minor grazes to fatalities was collected. This suggests that there was a culture of reporting injuries and a mechanism to forward the information on to be centrally collated – a paper trail from worksite to head office. Health and Safety may have been lacking by today’s standards but at least they knew what was going on; how much human harm the construction was wreaking.

By 1898 it is estimated that around 2,000 men were employed on site. The wide range of their occupations is revealed in the data on those injured. The ledger entries typically record – name, date of the incident, the job of the injured person and a brief description of the injury often with a mention of its cause.

During the approximately 7 years of construction I have identified 362 injuries among those doing the work. In analysing the data I have looked at the following aspects:

- Date of the injury and hence the number per year

- Fatalities

- Injuries involving fractured bones

- The role or job of the injured person

- The type of injury

- The part of the body injured

- The cause of the injury

- An attempt to classify the injuries as Minor, Moderate or Severe

Number of injuries per year.

- 1897 1

- 1898 88

- 1899 55

- 1900 48

- 1901 70

- 1902 31

- 1903 35

- 1904 34

- Total 362

Work began in the later part of 1897 with just a single mishap in October of that year. 1898 however was the most accident prone year of the 7 year undertaking, in particular the second half of the year. Whereas from January to June 1898 there were only between 0 and 5 accidents per month these rose to 11 in July, 2 in August, 28 in September and 15 in October. This was by far the most humanly harmful period of the endeavour. Thereafter monthly injuries only reached 10 in January and March 1901. In all other months the count was in single figures.

The frequency of injuries may be an indicator of the intensity of the construction works – how much activity was happening on site. If so then the works ramped up in 1898 to a peak in the autumn and thereafter settled to a somewhat less intense level winding down in the final 3 years of the undertaking.

However the frequency of injuries may also relate to how safely, or otherwise, construction activities were being performed. The relatively lower rate of injuries in the later years may reflect better, safer, working conditions, rather than less activity. One cannot be sure which was the principle factor in reducing injuries after 1898 – less activity, or better health and safety. Nevertheless the total number and types of injuries indicates that working conditions were hazardous by modern standards.

Fatalities

There were 11 fatal injuries connected with construction works, 1897-1904. The details of these, as recorded in the Midland Railway ledger, are listed below. Fatalities related to operation of the port in its early years are considered separately.

28/3/1898. J. O’Brian, Platelayer, killed by discharge of gelatine during blasting operation.

19/10/1898. J. Brown, Borer, struck by piece of rock and fell on head of drill which pierced his thorax.

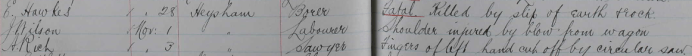

28/10/1898. E. Hawkes, Borer, killed by slip of earth and rock.

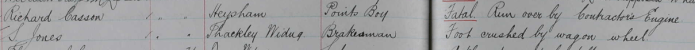

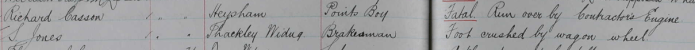

30/10/1899. Richard Casson, Points Boy, run over by contractors engine.

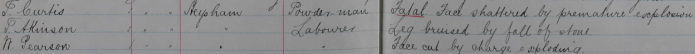

11/1/1900. F. Curtiss, Powderman, face shattered by premature explosion.

25/6/1900. J. McCowle, Labourer, crushed by piece of rock.

2/7/1900. J. Winfield, Platelayer, crushed by navvy bucket. [presumably steam powered excavator]

24/9/1900. J. O’Donnell, job not specified, crushed between buffers.

26/9/1902. K. Rilley, Labourer, crushed by fall of full skip into hold of steamer.

10/12/1902. G. Scorgie, Labourer, whilst drawing “soldier” the wind blew it over onto him.

21/11/1903. John Lucas, Labourer, crushed between buffers.

There were no deaths during 1901 or 1904. The manner of the death of K. Rilley in September 1902 suggests that by that stage the harbour, or access to it, was sufficiently well advanced that steam vessels could be used to transport the excavated waste away from the site. The death of J. O’Brian in March 1898 mentions “gelatine”. This suggests the use Gelatine Dynamite, also known as “blasting gelatin” or simply “jelly”. Its gel like consistency makes it easier to handle and manipulate and it was useful for excavating extremely hard rock. It is supposedly safer than Dynamide but its nitroglycerine content can leach out or “sweat”. The two deaths from explosions shows how hazardous blasting was. The term “Powderman” (F. Curtiss, January 1900) seems to harp back to the time of the use of gunpowder.

Injuries involving fractured bones

There were 32 injuries involving the fracture of a bone, representing 8.4% of all incidents. 12 of these were fractures of the long bones of the leg, a serious and debilitating injury that would result in a long period off work. These fell into 3 categories; (i) something falling onto or striking the worker – such as rock, stone, earth, sand, a water tank or a sleeper (8), (ii) being run over or struck by a wagon (3), and, (iii) the person themselves falling, which only accounted for 1 incident. There were 5 fractures of the long bones of the arm – 3 caused by material falling onto the person (a skip, rock and stone), and 2 cases were the worker themselves fell. G. Swintenbank, a Wagon Greaser, suffered a fracture of the pelvis when trapped by a wagon in April, 1900, and J Sharples a fracture of the ankle from the fall of a large stone in May, 1901.

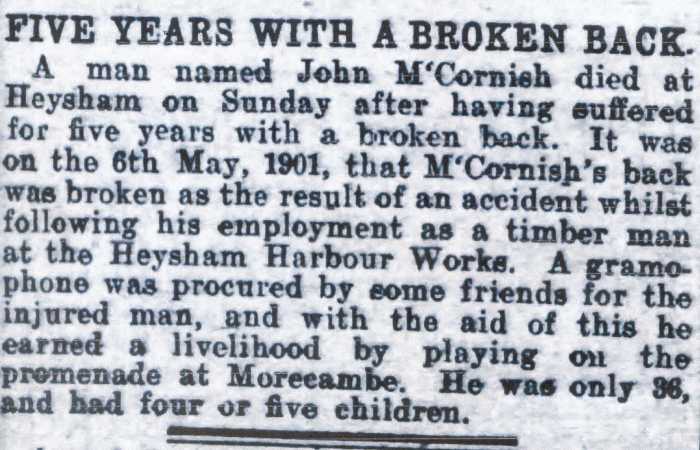

Other accidents caused 2 broken fingers, the fracture of a wrist after falling from some staging, a broken ankle from the fall of stone, 6 incidents of broken ribs from such things as being caught between buffers, slips and falls, being hit by falling stone, and one case due a collision between an engine and a wagon which sounds rather as if the workers was thrown from one or the other. Two grim incidents were a worker’s face being shattered by a premature explosion resulting in death, and a back broken by a fall likely resulting in paralysis. In contrast a broken collar bone from the fall from a truck seems rather trivial.

Who was being injured?

The list below of the types of workers injured during the construction provides an insight into the range of occupations employed in the works. However by far the most common job description is “Labourer” – 248 or 68.5% of all those recorded as suffering an injury. The job descriptions are those used in the ledger record some of which were of that era and are not used today. For example a “Rope Runner” was a Navvy term for a fireman, guard, shunter and general helper of the driver of a work-locomotive (Ref link). In alphabetical order, the numbers of injuries for each occupation, with some examples from the ledger record:

- Blacksmith 2

- Boilersmith 1

- Borer 3

- Boy 4

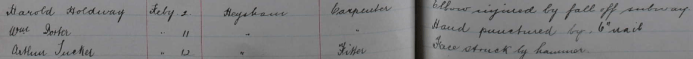

- Carpenter 11

- Cleaner 1

- Crane Driver 4

- Fireman 1

- Fitter 8

- Fitter’s Apprentice 1

- Gral Driver 1

- Greaser 1

- Horse Driver 3

- Loco Driver 4

- Mason 3

- Mate on Dredger 1

- Miner 1

- Navvy 1

- Navvy/Excavator Driver 1

- Pipper 2

- Labourer 248

- Pitcher 2

- Platelayer/Ganger 13

- Points Boy 1

- Pointsman 1

- Powderman 3

- Pump Driver 1

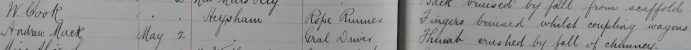

- Rope Runner 11

- Sawyer 3

- Scappler 1

- Shunter 1

- Slasher 1

- Striker 2

- Timberman 3

- Wagon Coupler 1

- Wagon Greaser 7

- Wagon Stopper 1

- Wheelman 4

- Winch Driver 1

- Not Specified 3

Type of Injury

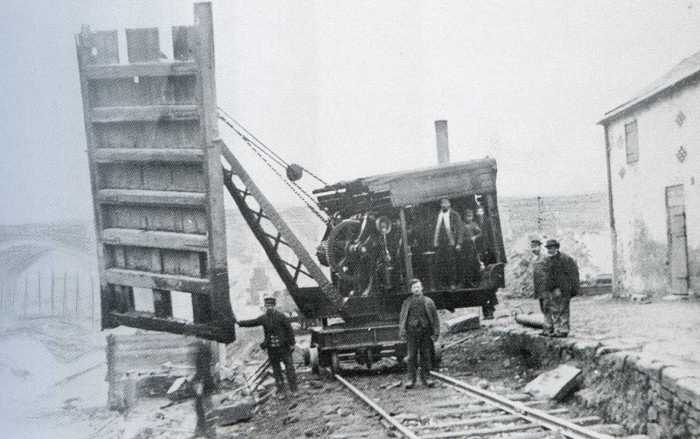

The type of injuries suffered reflects the working environment, the nature of the undertaking and the machinery being used. There was blasting in a nearby quarry to obtain material for the sea walls. Steam powered navvies (excavators) were used to hollow out the harbour basin. Waste material was moved around in tipper wagons on temporary rails.

Crush injuries from the fall of rock, stone, earth or metal objects onto workers are the most frequently documented type of injury. I have stuck with this classification where it is specifically mentioned in the report. However I have used the term “pinch” where workers were caught between two objects, such as the buffers of wagons or skips. These terms do not in themselves indicate the severity of the injury. “Crush” might be that of a finger, thumb, toe, hand, foot – or the whole person. The more minor events were much the more common. If the injury involved the fracture of a bone it is classified under that category even if, for example, there may have been a crush, pinch or blunt blow element. In the list below each injury is counted just once using the main factor that describes its nature.

Even minor injuries are recorded such as sprains and grazes. From the ledger entry it is difficult to judge how severe bruises or cuts were but in an era before antibiotics, and working in a dirty environment, any break of the skin could lead to infection and septicaemia, but there is no way to determine how much of an issue that was apart from one case where a hand was poisoned by a thorn. The two “amputations” were loss of a finger, one by a saw, the other by a rock. The four stab injuries were – a drill penetrating the chest, a pick entering the abdomen, a 6 inch nail puncturing a hand and a piece of steel impaled in a wrist. A shoulder was dislocated by the impact of buffers. In the records where the type of injury is specified there were:

- Crush 80

- Bruising 71

- Bruising and Cut 2

- Cut 38

- Fracture 32

- Pinch 20

- Sprain 13

- Blow 19

- Graze 4

- Stab 4

- Amputation 2

- Burn/Scald/Scorch 4

Also – 1 concussion, 1 infection, 1 joint dislocation, 1 strain and in one case the person was merely described as shaken.

Body part injured

By the end of the nineteenth century machinery, such the steam powered excavator, was in use in civil engineering works like the construction of Heysham Harbour. The building of the Settle – Carlisle Railway in the 1870’s, another Midland Railway project, was the last major purely navvy pick, shovel and barrow undertaking. Nevertheless much of the work at Heysham involved manual labour and therefore not surprisingly many injuries involved the hands.

Taken together injuries to fingers, thumbs and hands accounted for 86 of the 345 accidents (25%) where a body part was specified. Those to the feet and toes were 56 (16.2%). Twelve of the 58 (20.7%) leg injuries (excludes ankles), and 5 of the 15 arm injuries (33.3%) were fractures. Seven of the 11 facial injuries (63.4%) were due to explosions . This suggests a close proximity to the detonation and were likely suffered by those setting the charge. Two of the back injuries probably involved a major spinal injury as they are described respectively as “back broken by fall” and “back severely injured by falling down sump”. A third case may also not have had a good outcome considering its description – “back injured thrown from footplate of steam navvy”. The breakdown of the body part injured is listed below.

- Finger 60

- Thumb 13

- Hand 16

- Arm 15

- Leg 58

- Foot 37

- Ankle 11

- Toe 19

- Head 36

- Face 11

- Back 15

There were 9 injuries involving the ribs with an additional 4 affecting the chest in other ways, 9 to a knee, 9 a shoulder, 4 a wrist, 2 an elbow, 2 the nose, 2 to an eye, 2 to the jaw, 2 to the flank, along with single injuries affecting – both arm & leg, a hip, the chin, a shin, a collar bone, the neck, the abdomen, the pelvis, and one just described as affecting the skin. In 17 cases the body part harmed was not specified.

Cause of Injury

- Equipment & tools 71

- Rolling Stock 60

- Stone 50

- Rock 25

- Fall of the person 44

- Timber 23

- Explosion 14

- Skip 15

- Rail 13

- Earth or Sand 10

- Metal Object 13

There was one injury related to each of the following: brick, the fall of a chimney, a derailment, an incident with a horse, a mishap with a rubble box, slag, a thorn, some wire. There were 16 instances were no cause is specified.

Most of the cases involving Stone, Rock, Timber, Earth and Sand were due to these falling onto the workers. Taken together they represent 107 or 30% of all incidents. The comments in the records range from “Toe injured by rock”, through “Leg fractured by fall of rock” to a fatality caused by being “Crushed by piece of rock”. The term “Fall” in the above list are cases where the injury was due to the worker themselves suffering a fall.

Equipment, the tools and materials, used in the excavation and construction, were frequent contributors to injuries. Objects in motion or the operation of machinery appear to have been particular risk factors. Such things as being hit by swinging chains (9), the excavator bucket (4), parts of a crane (4), a wire band (1), or a finger caught in gearing cogs or a thumb in a stone crushing machine.

The use of levers or “sprags”, a Navvy term for a wooden stick or pole (ref link), are mentioned 12 times as the main factor in an injury. A range of hand tools were also implicated – hammers (5), picks/shovels/forks (6), saws (2), a crowbar, a drill, a spanner, and on 3 occasions mishaps with nails.

Injuries caused by rolling stock were predominately incidents with rail mounted wagons. These were likely of the navvy tipper type used for transporting excavated earth. These were chunky ungainly vehicles taller than the average navvy and ran on uneven temporary tracks. Controlling them must have been an art and particular skill. The records of injuries reveal there were 3 main hazards – being run over by a wheel, being knocked by or trapped between buffers, and dealing with couplings. A couple of incidents were due to collisions. In 5 cases the accident involved a locomotive engine, one resulted from being thrown from the steam excavator, 2 involved horse carts, and 2 hand trucks.

The term “Skip” refers to large buckets used, for example, for lifting men and muck in and out of deep holes or trenches (ref link), or the hold of a ship. Injuries could occur when maneuvering and handling these. Of the 15 incidents 4 were due to the skip falling and 6 where a part of the body was crushed or trapped by a skip. In 5 the description is brief and vague just documenting bruising or that an arm was injured.

The 14 injuries from explosions can be divided into those resulting from a problem with the explosive material, e.g. explosion of the fuse or cap or premature explosion of the charge. This is explicitly mentioned in 7 cases – and this may also have been the scenario in two further cases were the face was scorched suggesting a close proximity to an explosion flash. The remaining injuries were presumably cause by the explosion event e.g. by flying rocks and debris.

Injuries caused by rail seem to be where a rail fell or was dropped. 11 of the 13 mishaps were to fingers, toes or feet, with the exception being a cut to the forehead by a falling rail. Whether the rail involved was part of the permanent way of the harbour or for the temporary tracks along which the navvy tipper wagons ran is not specified. There were no rail related injuries in 1902. The 6 occurring before that date, i.e. during the earlier phase of construction seem, to me, more likely to relate the temporary tracks.

There were 13 miscellaneous injuries due to metal objects; pieces of iron, steel, a metal nut, a bolt, a casting, a metal bar. The body part affected was equally as divers – the jaw (2), head (3), finger, thumb, toe, foot, knee, wrist, shin and eye. The frequent modes of impact were either the object being dropped or flying through the air.

Severity of Injuries

Using the description of the injuries and their nature I have tried to classify the severity of each; excluding those accidents that were fatal. The details recorded are usually quite brief, just a few words, so making this judgement is a little arbitrary involving some educated guess work. However I think this helps to judge the mix of accidents that were occurring during the construction, how hazardous a working environment it was, and the culture of reporting and recording the incidents. I have used the categories of “Minor”, “Moderate” and “Severe” to grade the injuries. Such injuries as grazes and sprains are clearly minor. Bruising is more difficult to judge but if it was of a finger, or thumb or toe I have assessed it as minor, whereas bruising to a more vital part of the body may be more significant. Head injuries I have classed as at least moderate unless the record says specifically otherwise. Leg and arm fractures and major crush injuries I have labelled as severe. On this basis the figures as thus:

- Minor Injuries 244

- Moderate Injuries 79

- Severe Injuries 28

- Fatalities 11

- Total 362

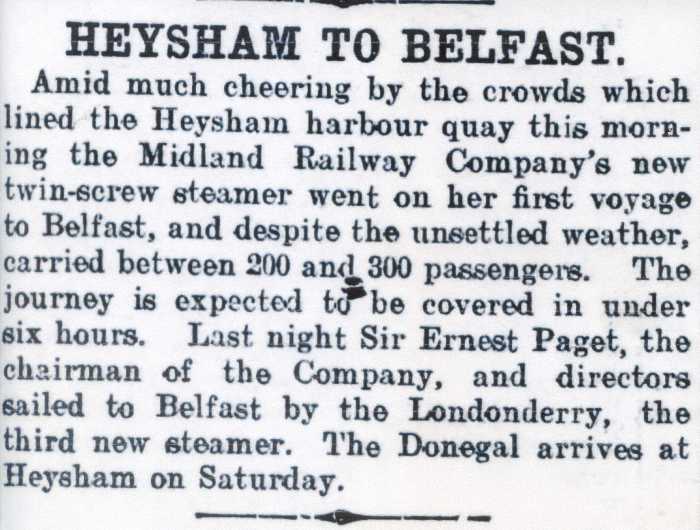

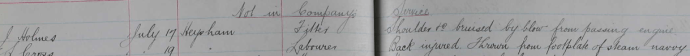

Injuries after 1904

The first ship to dock at Heysham was the Midland Railway vessel “Antrim”. She arrived on 31 May 1904. The first passenger sailing was on 13th August that year. There appears to be little overlap in injuries incurred during construction of the harbour with those associated with its operation. There were 8 injuries in 1904 that seems related to harbour operations. The first of these was on the 8th July when a Second Engineer tore a fingernail on a nail. There was then one incident in August where a Deckhand was found drowned, one in October affecting a member of the Goods Dept, 4 in November (two Deck Hands, a Goods Porter and a Loco Inspector), and one in December when the Harbour Master broke his leg in a fall.

In 1905 there were two injuries that might be attributed to finishing works in the construction. On the 2nd February a Labourer bruised his leg on a coping stone and on the 7th June a Sawyer cut his thumb on a piece of iron. All other recorded injuries for that year appear to be related to the various tasks and operations of an active port. The staff affected included – a fireman, a derrick driver, numerous deck hands and a ship’s captain, dock porters, two ships’ cooks, the mate on a dredger, a quayman, a docker, and a holdsman (someone who works in a ship’s hold).

After 1904, and completion of the port, injuries become much less frequent; at least as recorded in the Midland Railway ledger extending up to 1920. The apparant sparsity makes one wonder whether the records are complete. However the rates documented are as follows:

- 1905 16

- 1906 8

- 1914 2

- 1915 1

- 1916 2

- 1917 2

- 1918 5

- 1919 6

- 1920 4

- Total 46

Between 1905 and 1920 two fatalities are documented, both in 1905:

19/7/1905 J. Clarke. Caught by capstan rope.

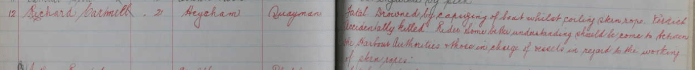

21/6/1905 Richard Cartmell. Quayman. Drowned by capsizing of boat whilst coiling stern rope. The verdict at the inquest into his death was “Accidental” but a rider was added; that “some better understanding should be come to between the Harbour Authorities and those in charge of vessels in regard to the working of stern ropes”.

Using the criteria defined above for categorising the injuries in the first 15 years of operation up to 1920 there were: 27 Minor, 11 Moderate and 6 Severe. The “Severe” cases are listed below with the details recorded in the Midland Railway ledger.

26/2/1905. J. Gillespie. Captain of SS Langton. Spine fracture and head cut by fall down stoke hold.

14/08/1905. T. Blackburn. Dock staff. Wrist fractures by fall into hold of steamer.

11/10/1905. J. Longuire. Traffic Dept – Dock Porter. Leg broken and crushed by fall of pig iron.

17/12/1905. G. Rupp . Hotel Staff – chef. Thigh fractured by fall into cattle subway.

08/06/1918. C. Jones. Mate. Hand poisoned by piece of wire.

21/3/1919. R. Newman. Deck Hand. Thigh fractured by fall of 10 feet.